Focus on Me: Illicit Wildlife Trade is Fauna-Centric

Wildlife also includes plants

What do you think of when you hear the word ‘wildlife’? Almost certainly an animal — and perhaps that’s a problem. Our inability to recognize plants as wildlife is known as “plant blindness”.

Coined by Elisabeth Schlusser and James Wandersee almost twenty (20) years ago, “plant blindness” describes the tendency of people to overlook plants, and treat them as merely ‘the background’ of animal life (Wandersee & Schussler, 1999). Plant blindness feeds into the human-centered paradigm. Animals, especially humans, are seen as superior to plants, hindering our grasp of the crucial role that plants play in our ecosystems, well-being, and survival. However, this phenomenon of privileging animals over plants in society, and consequently, policy and law, is nothing new, as this mindset has long been evident in the lack of funding and interest in plant conservation.

Within wild flora, most research is focused on deforestation and the related issue of illegal logging, and by extension, this has led to a geographically constrained focus, with most attention on tropical forests (Goettsch et al., 2015). However, wild plants are often hidden ingredients in everyday products. Flora species from all ecosystems, such as orchids or cacti that grow in arid lands, are remarkably widespread but very often overlooked, thus, also requiring consideration.

Current Practices

ASEAN countries are home to abundant biodiversity areas. The Philippines alone is home to 5% of the world’s flora and ranks fifth worldwide in terms of number of plant species, and is also the home to over 700 threatened species, making it one of the world’s most important conservation sites. However, the government has not given enough attention to these natural treasures. Despite reforestation efforts such as the National Greening Program (NGP) of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), there has been no systematic education in schools about our natural environments. Moreover, not enough attention has been given to the value of plants and wildlife in these forests for the sake of diversity and the perpetuation of our natural environment.

The DENR issued an Administrative Order 11-2017 providing an updated list of threatened plant species across the country, showing that 179 species are critically endangered, 254 endangered, 405 vulnerable, and 145 threatened.

Endangered Species of Flora vs. Fauna

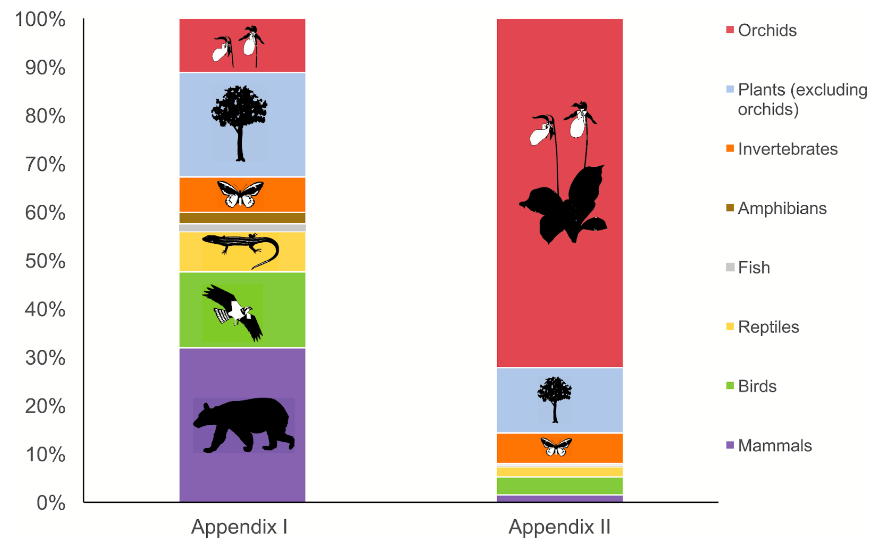

Taxonomic breakdown of CITES Appendices I and II. From Hinsley et al. (2018, p. 441)

The lack of data and research on threatened plants species in developing countries (Agduma et al., 2023; Troudet et al., 2017; Tantipisanuh & Gale, 2018), such as the Philippines, is particularly puzzling given that plants constitute a large percentage of the species protected by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES).

The CITES is an international agreement signed by 184 governmental parties, including the Philippines. It primarily safeguards wildlife products such as plants and animals from illegal trade, domestication, and overexploitation to ensure their survival despite the extreme anthropogenic pressures.

At the national level, the Philippine government also implements the Wildlife Resources Conservation and Protection Act (Republic Act No. 9147) to enable the government to comprehensively manage and conserve the wildlife resources of the country.

Illegal wildlife trade is a multi-billion-dollar industry with an estimated annual value of between USD 10 and 23 billion (United Nations Environment Programme, 2016), making it the fourth most profitable illegal business, just behind narcotics, human trafficking, and firearms. It includes land and marine animals, plants, and timber collected illicitly and unsustainably. According to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), illegal wildlife trade is second to habitat destruction in terms of threat to the survival of endangered species. In the Philippines alone, Asian Development Bank (2019) reported that the value of the Illegal Wildlife Trade has been estimated at USD 1 billion, including the market value of the animals along with their ecological role and the damage to habitats incurred during poaching.

Recent research by Margulies et al. (2019) found that Illegal Wildlife Trade (IWT) policy and funding by governments and conservation organizations continue to focus efforts and funding on rhinos, elephants, and other charismatic species. Yet more plant species go extinct annually and more plants are listed on CITES (with 30,000 plants vs. 5,000 animals).

Trafficking to Extinction: The Illegal Plant Trade in the Philippines

The Illegal plant trade has a higher economic value than illegal animal trade and the damage done by illegal harvesters can destroy whole ecosystems, costing millions to repair.

On December 24, 2020, the Bureau of Customs (BOC) reported that seventy-three (73) kilograms of agarwood chips, worth approximately Php 62 million, were confiscated at the Port of Davao. These were scheduled to be shipped to Vietnam. In 2022, the BOC again reported the interception of 28 kilos of agarwood worth PHP2.4 million in Pasay City.

Although agarwood is classified under the “Appendix 2” of the CITES, it is widely gathered as one of the world’s most expensive natural raw materials. Appendix 2 of the CITES lists all species which although not necessarily now threatened with extinction may become so unless trade in specimens of such species is subject to strict regulation, and, furthermore, other species which must be subject to regulation in order that trade in specimens of certain species may be brought under effective control. In the country, first-class agarwood is traded at PHP750,000 per kilogram (Meniano, 2019). The resin-embedded wood is valued in Arabic-middle Eastern culture for its distinctive fragrance and is used for incense and perfumes. DENR Region 8 Regional Director Crizaldy Barcelo revealed in the aforecited report (Meniano, 2019) that some traders from Mindanao have been reported in the area, expressing their intention to buy agarwood – sometimes described as liquid gold or wood of the gods – extracted from host trees locally known as Lapnisan and Lanete.

Another report by Zuasola (2022) revealed massive and indiscriminate cutting of wild trees in the protected mountain range of Davao Oriental. Villagers in the area have started shifting from farming and fishing to participation in the illegal agarwood trade. A science professor at the government-run Davao Oriental State University (DOrSU) remarked that former fishermen told them that in a week, they earned at least P50,000 from extracting agarwood. This is in contrast to what they previously earned (P10,000) during that same period from fishing at Pujada Bay.

Nepenthes sibuyanensis is endemic to Sibuyan Island in the Philippines, where it grows on Mount Guiting-Guiting (International Carnivorous Plant Society, n.d.)

Other plants are also at risk. A pitcher plant species classified as Nepenthes sibuyanensis, is one of the endemic plants found in Mt. Guiting-Guiting, Romblon. It is carnivorous and has modified leaves called pitfall traps that are shaped like water “pitchers,” hence the name.

In early 2021, the BOC and the DENR seized 276 imported carnivorous plants worth PHP150,000 from a cargo warehouse in Pasay City (Patinio, 2021). A picture of Mt. Malindig “hikers” posing and taking wild plants went viral after learning that the plant they took was a pitcher plant (Malasig, 2021). Collecting rare and endangered wild plants like pitcher plants is strictly prohibited.

Amesiella Monticola is an endangered, tiny orchid species native to Central Luzon Mountains, and highly sought after by miniature growers. (HighDesertOrchids, n.d.)

Collecting plants may provide a source of calm and joy in stressful times and has been a source of livelihood for many entrepreneurs. However, this has caused concerns regarding the irresponsible use of national resources. Plantitos and plantitas, a vernacular for plant hobbyists and collectors, became a widespread fad after the Philippines was placed on lockdown in 2019, to avoid the possible spread of COVID-19.

Unfortunately, the gardening craze has also led to endangered species being dug up from mountains and forests at alarming rates. According to Hinsley (2018) who looked at the role of online platforms in the illegal orchid trade, there is considerable overlap between the legal and illegal online trade. A 2017 study has shown that more than 365 protected plant species are openly traded via Amazon and eBay (CITES, 2017). Phelps and Webb (2015), in the first in-depth study of the trade of wild-collected ornamental plants in continental Southeast Asia, discovered that there is a large degree of underreporting of the illegal trade in ornamental plants. Orchids, tree ferns, and molave bonsai, which are the most common and popular garden and house plant species in the Philippines, are among the ten (10) commonly poached threatened plants in the country according to the DAO No. 2017-11.

Noting the growing number of plant sellers and collectors in the Philippines and reports of plant poaching, the DENR has issued a warning against the “collection of plants that are naturally sprouting in the wild or in its rainforest environment, especially within the protected areas.

The Way Ahead: Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) adopted in COP 15 represents the most ambitious global agreement on biodiversity in the history of environmental governance and will serve as the world's framework for actions taken at all levels to safeguard and restore biodiversity under 23 targets to be achieved by 2030 and towards four long-term goals for 2050. The adoption of this ambitious and robust framework represents a remarkable demonstration of multilateralism and international cooperation and an important first milestone of a long process that aims to halt biodiversity loss. The implementation journey has just started and, for the Framework to be successful, there is a need for Governments to take urgent action at all levels.

Among the twenty-three (23) GBF targets to be achieved by 2030, the plan includes concrete measures to help stop and reverse nature loss, including placing 30% of the planet and 30% of degraded ecosystems under protection by 2030. It also contains proposals to increase finance to developing countries. The targets that are directly applicable would be: (a) Target 5 on preventing overexploitation which ensures that the use, harvesting, and trade of wild species is sustainable, safe and legal; (b) Target 6 on eliminating, minimizing, reducing and mitigating the impacts of invasive alien species on biodiversity and ecosystem services; and (c) Target 9 on sustainable management and use of wild species thereby providing social, economic and environmental benefits for people, especially those dependent on biodiversity-based activities.

Even as illegal trade in wildlife now receives considerable attention in conservation circles, not much attention is paid to the species-jeopardizing illegal trade in plants. This is particularly a concern in the face of other pressing global issues such as climate change, economic development, and social issues that may take priority over biodiversity conservation.

As a way forward, public awareness and education are essential for promoting biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. Education and awareness-raising campaigns should target all sectors of society, including youth, women, persons with disabilities, indigenous people and local communities. In addition, countries need to strengthen their national biodiversity strategies and action plans to align with the objectives of the KMGBF. This will require effective engagement of all stakeholders and sectors. In the Philippines, the Philippine Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (PBSAP) is the country's roadmap to conserve its biodiversity and achieve its vision that “by 2028, biodiversity is restored and rehabilitated, valued, effectively managed and secured, maintaining ecosystem services to sustain healthy, resilient Filipino communities and delivering benefits to all.” It is currently being updated to reflect the country’s commitments under the KMGBF.

By gaining a deeper understanding of biodiversity in the Philippines, we can better and more sustainably protect critical ecosystems in the country from the increasing threats posed by human activities. Plants were the beginning and remain the foundation of all humanly visible life. They are worth appreciating and protecting.

Note: Jenn Tayamin was a legal intern from the 2023 Summer Internship Program of Parabukas. This article is her individual contribution to on-going discourse on her chosen environmental issue.

References:

Agduma, A. R., Garcia, F. G., Cabasan, M. T., Pimentel, J., Ele, R. J., Rubio, M., Murray, S., Hilario-Husain, B. A., Cruz, K. C. D., Abdullah, S., Balase, S. M., & Tanalgo, K. C. (2023). Overview of priorities, threats, and challenges to biodiversity conservation in the southern Philippines. Regional Sustainability, 4(2), 203–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsus.2023.05.003

Asian Development Bank. (March 2019). Addressing Illegal Wildlife Trade in the Philippines. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/490006/addressing-illegal-wildlife-trade-philippines.pdf

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. (2017). CITES-listed medicinal plant species (PC23 Inf. 10). https://cites.org/sites/default/files/eng/com/pc/23/inf/E-PC23-Inf-10.pdf

Goettsch, B., Hilton-Taylor, C., Cruz-Piñón, G., Duffy, J. P., Frances, A., Hernández, H. M., Inger, R., Pollock, C., Schipper, J., Superina, M., Taylor, N. P., Tognelli, M., Abba, A. M., Arias, S., Arreola-Nava, H. J., Baker, M. A., Bárcenas, R. T., Barrios, D., Braun, P., Butterworth, C. A., … Gaston, K. J. (2015). High proportion of cactus species are threatened with extinction. Nature Plants, 1(10). https://doi.org/10.1038/nplants.2015.142

HighDesertOrchids. (n.d.). Reddit. https://www.reddit.com/r/orchids/comments/ekp3nh/amesiella_monticola_one_of_three_species_of_the/

Hinsley, A. (2018). The role of online platforms in the illegal orchid trade from South East Asia. Geneva: The Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime.

International Carnivorous Plant Society. (n.d.). https://legacy.carnivorousplants.org/cpn/Species/v27n1p18_23.html

IPBES. (2019). Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6417333

Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. (18 Dec. 2022). CBD/COP/15/L.25

Malasig, J. (2021). No illegal collection of wild plants: DENR warns as photo of Mt. Malindig ‘hikers’ with pitcher plant go viral. PhilStar. https://interaksyon.philstar.com/trends-spotlights/2021/02/09/185169/no-illegal-collection-of-wild-plants-denr-warns-as-photo-of-mt-malindig-hikers-with-pitcher-plant-go-viral/

Margulies, J. D., Bullough, L-A., Hinsley, A., Ingram, D.J., Cowell, C. et al. (2019). Illegal wildlife trade and the persistence of "plant blindness". Plants, People, Planet 1: 173-182.

Meniano, S. (2019). ‘Liquid gold’ rush endangers Region 8 forest: DENR. PNA. https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1081546

Patinio, F. (2021). BOC seizes 276 imported carnivorous plants in Pasay warehouse. PNA. https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1146262

Phelps, J., & Webb, E. L. (2015). “Invisible” wildlife trades: Southeast Asia’s undocumented illegal trade in wild ornamental plants. Biological Conservation, 186, 296-305.

Philippine Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (PBSAP) 2015-2028 (2015) https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/phi189948.pdf

Tantipisanuh, N., & Gale, G. (2018). Identification of biodiversity hotspot in national level – Importance of unpublished data. Global Ecology and Conservation, 13, e00377. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2018.e00377

Troudet, J., Grandcolas, P., Blin, A., Vignes-Lebbe, R., & Legendre, F. (2017). Taxonomic bias in biodiversity data and societal preferences. Scientific Reports, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-09084-6

United Nations Environment Programme (2016). The rise of environmental crime: A growing threat to natural resources, peace, development and security. https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/7662.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, World Wildlife Crime Report 2020: Trafficking in protected species. (United Nations, 2020).

Updated National List of Threatened Philippine Plants and their Categories, DENR Administrative Order (DAO) No. 2017-11 (2017). https://www.informea.org/sites/default/files/legislation/DENR%20Order%2011%202017%20%28Updated%20National%20List%20of%20Threatened%20Plants%20and%20their%20Categories%29.pdf

Wandersee, J. H., & Schussler, E. E. (1999). Preventing Plant Blindness. The American Biology Teacher, 61(2), 82–86. https://doi.org/10.2307/4450624

Zuasola, F. (2022). Davao Oriental farmers, fishers turn to illegal trade of ‘wood of the gods’. RAPPLER. https://www.rappler.com/nation/mindanao/farmers-fishers-turn-illegal-trade-wood-gods-davao-oriental/